The Arctic, a region greatly affected by climate change, is experiencing some of the highest rates of warming compared to the rest of the globe. Although much research has focused on understanding the resulting changes in these high-latitude ocean regions, there is a noticeable gap in coastal zone monitoring. This coastal area is often the most utilized and important to local communities. Nunatsiavut, an Inuit self-governing territory located on the northernmost coast of Labrador in Canada, is one such coastal region.

In Nunatsiavut, Inuit depend heavily on the land and coastal ocean for travel, traditional activities, and food sources. In fact, the five communities – Rigolet, Makkovik, Postville, Hopedale and Nain – are all located close to the mouths of various inlets, bays and fjords where the interplay of freshwater and seawater create biologically productive environments. Fishing in these coastal waters is particularly important culturally and provides food stability for some families due to high grocery prices in this remote region. However, with the emergence of increasing climate change effects, food security, travel routes and access to ancestral homes are potentially being threatened.

From using and experiencing this coastal area, the Inuit communities have gained generations of knowledge about their local environment, and how climate change is affecting it. This type of expertise is, however, often not used in scientific studies. Dr. Eric Oliver, a physical oceanographer with roots in Nunatsiavut, is aiming to change that.

Oliver is part of a team of individuals studying the Nunatsiavut coastal environment. This team includes academics spanning several disciplines in the natural and social sciences as well as local experts and knowledge holders. Their project is motivated by uncertainty in long-term change and guided by Nunatsiavut community interests. This work aims to perform “community-out” rather than “ship-in” science, combining past and present Inuit knowledge with community-led scientific monitoring.

Figure 1: Participatory community mapping (photo credit: Breanna Bishop)

This work with the Nunatsiavut communities started in 2018 – work which is rooted in relationships and conversations. One aspect of the project, led by PhD student Breanna Bishop, focuses on participatory mapping. Their approach has community members share their vast knowledge, detailing information about both short- and long-term trends in various ocean and sea-ice features. So far, work has focused on compiling observations from when the coastal area is seasonally ice-covered, as this is a time of year experiencing significant change. Over the winter months, the ice facilitates travel to ancestral homes and fishing for sustenance; these activities are the foundation of the community’s understanding of the sea-ice and how climate change might be affecting ice quality or fish availability.

Figure 2: Example results of community mapping (photo credit: Breanna Bishop)

Through conversations with communities, conceptual models have emerged. For example, a very complex and nuanced understanding of the landfast ice dynamics near Makkovik was detailed by community members – something, Oliver notes, would have taken scientists a long time to flesh out on their own. Landfast ice is the ice directly attached to the shoreline. Every year there are transition periods in late fall and late spring when travel is difficult; these are periods when people can neither travel by sled nor by boat as ice is either forming (in the fall) or breaking up (in the spring). The ice-making season (December-January) is a particularly important time of year and is seeing large changes. Community members describe these ice-making months as the time when there is overlap with the darkest and coldest days. If the sea-ice doesn’t develop during this period, it won’t matter how cold it gets later in the season as the days are too long and sunny after this window. There has also been a higher frequency of storms during the ice-forming season in recent years. These storms lengthen the ice-forming period, which inhibits the travel of the community for a longer period of time and limits their access to important ancestral areas and food sources.

This detailed, multi-generational knowledge is the foundation which is being built upon by contemporary observations coming out of the Nunatsiavut communities. Dr. Emma Harrison, a postdoctoral fellow, is currently working with local experts Ron Webb and Gus Dicker from Nain. These experts, also referred to as Land Observers, relay rich observations about the weather, coastal currents, and ice conditions that they witness daily.

To supplement these narrative-based observations, community-based monitoring has also been implemented. Oliver comments that, “under climate change, these [coastal] systems are changing so quickly and in ways that mean local knowledge [alone] is no longer as good at predicting what to expect.” Full-time Inuit Research Coordinators have therefore been hired in 4 out of 5 Nunatsiavut communities to perform field work under the Sustainable Nunatsiavut Future’s project. Due to pandemic travel restrictions, this monitoring has been truly community-based with little hands-on help from scientists. It therefore relies on RBR oceanographic instruments that produce research-quality data, while being rugged and easy to use for the Research Coordinators.

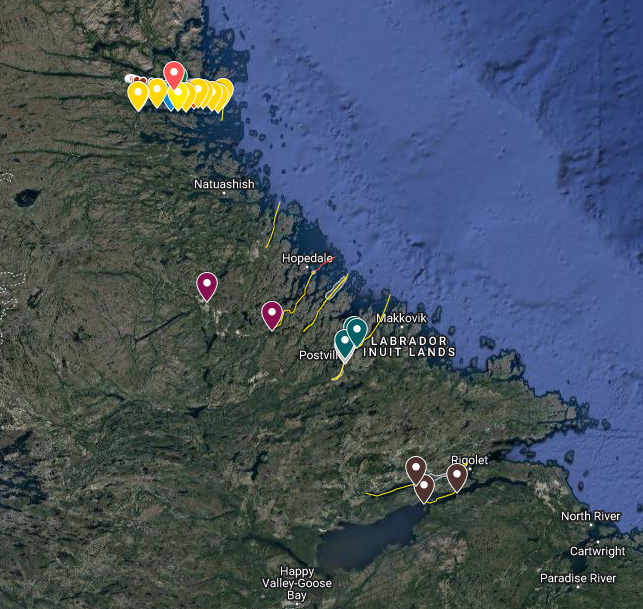

Figure 3: The mapped monitoring plan created during community fieldwork planning sessions. The yellow lines are the CTD sampling transects.

The current monitoring plan, designed by the community, concentrates on sampling transects of several unique fjord-like systems in the area. These transects mainly focus on measuring snow and ice thickness and taking through-ice temperature and salinity profiles using RBRconcerto³ C.T.D instruments. Three of the RBR CTDs have been equipped with biogeochemical sensors to measure oxygen, chlorophyll, dissolved organic matter, and turbidity. This sampling strategy adds a quantitative metric to the existing monitoring, effectively tracking changes to salinity and temperature in the coastal inlets to better understand what factors set the coastal ocean conditions. The data from the monitoring program compliments the local knowledge and is an important tool in understanding how climate change will affect the long-term productivity and fishing sustainability of this region.

The outcome of this multi-faceted work is a detailed view of the Nunatsiavut coastal system. This is, however, only the beginning. Oliver and his colleagues are iteratively working on this research process, reflecting and revising methods frequently, and aiming to create more relationships in the community. Scientific findings are certainly an important product of this work, but Dr. Oliver notes that the methods that he and his team are building are perhaps the main and most exciting outcome, and hopefully stands as an example for future work in other Arctic regions.

This story was also published in the ECO Summer 2022 digital edition.

Story by Krysten Rutherford