Speed of sound in water

What is speed of sound in water and why do we measure it?

Sound-speed in water is a quantification of how fast sounds travel in water. The speed of sound in water depends on temperature, salinity, and pressure, and is therefore not uniform throughout different water environments. In the oceans, the speed of sound varies between 1450m/s and 1570m/s. It increases by approximately 1.3m/s per 1PSU increase in salinity, 4.5m/s per 1°C increase in temperature, and 1.7m/s per 1dbar increase in pressure.

Sound propagation in particular depends on variations in sound-speed (Leroy and Parthiot, 1998). Therefore, when studying ocean acoustics and ocean soundscapes, the speed of sound is often an important variable to consider for many oceanographers.

Table of contents

- What is speed of sound in water and why do we measure it?

- How can we measure the speed of sound in water?

- How do we practically measure the speed of sound in water?

- What equations are available to calculate sound-speed in water?

- Instruments to measure the speed of sound in water

- From the field: related user stories

- References and additional resources

How can we measure the speed of sound in water?

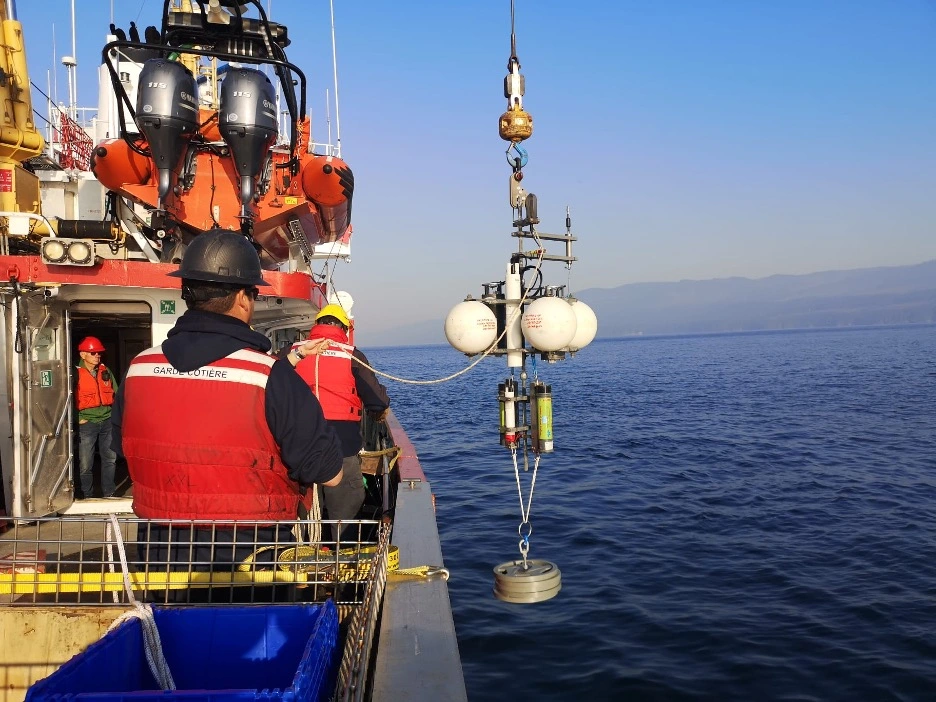

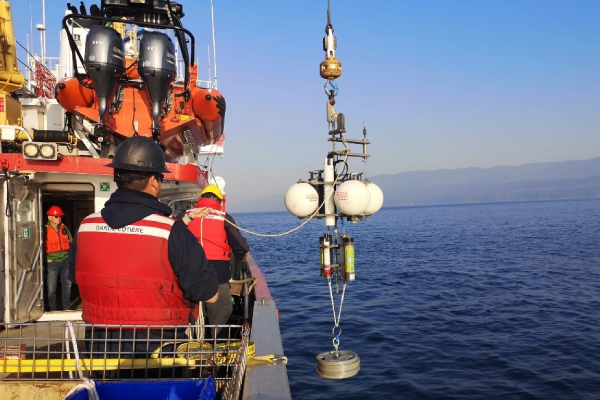

There are two ways to measure speed of sound in water in situ: i) by using a small acoustic signal which is sent to a receiver at a known distance, like in a sound velocity profiler; or ii) by measuring the variables affecting sound velocity in water (salinity, temperature, and pressure) with a CTD and calculating sound-speed empirically. Which method is best for you depends on your application, your measurement goals, and also, what equipment you have available.

Should you use a sound velocity profiler or a CTD to measure speed of sound?

That depends on the purpose of your measurement. If your only purpose is to measure sound-speed, for example to correct sonar data for bathymetric measurements or for underwater navigation, a sound velocity profiler might be the correct choice. A time-of-flight sound velocity profiler is fluid agnostic - since it only measures time, it will work the exact same in every liquid. In contrast, a CTD will likely need to be recalibrated for use in fluids that are significantly different than seawater.

Regardless, if you are looking to measure anything more than speed of sound, you will need a CTD. Conductivity, temperature, and pressure (depth) are foundational properties in oceanography, and are required in most (if not all) TEOS-10 equations (Thermodynamic Equation Of Seawater - 2010), the international standard for calculating the thermodynamic properties of seawater. This is particularly evident for salinity calculations, which are necessary for understanding both local and global processes. Using a CTD has the distinct advantage of collecting data for both these fundamental properties and also for speed of sound - all from the same measurement!

Furthermore, since CTDs have been used to calculate sound-speed for much longer than sound velocity profilers, most historical speed of sound data will have been calculated from CTD measurements. If you want to compare your data to the decades of historical speed of sound data that have been calculated from CTD measurements, you should continue using a CTD to calculate speed of sound, for continuity.

How do we practically measure the speed of sound in water with a CTD?

Over the last 50 years, numerous equations have been developed to describe sound velocity in seawater. The original equations developed were based on precise lab experiments that measured the time for a sound pulse to travel a known distance at various combinations of temperature, salinity, and pressure (Wilson, 1959). From these experiments, scientists fit the data with complex polynomials such that temperature, salinity, and pressure simply need to be plugged into these equations to calculate sound-speed for any given parcel of water (see Wilson, 1960; Del Grosso, 1974; Chen and Millero, 1977).

With these equations, measurements from a CTD can be directly used to calculate the speed of sound at any location, and can act like a sound velocity profiler measuring the speed of sound throughout the water column. RBR’s Ruskin software directly calculates the speed of sound from the data collected by the instrument. The user can select one of three equations - UNESCO, Del Grosso, or Wilson - directly in the Ruskin application, or calculate sound-speed using the RSKtools (Matlab) and pyRSKtools (Python) toolkits.

What equations are available to calculate sound-speed in water?

There are three common equations used to calculate sound-speed in seawater: Wilson (1960; the first accurate measurements of sound-speed in distilled water and seawater), Del Grosso (1974), and Chen and Millero (1977, currently the UNESCO standard). See Dushaw et al. (1993) for a summary of these equations and associated laboratory experiments. In addition, see Wong and Zhu (1995) for the full list of coefficients for the UNESCO and Del Grosso equations using the ITS-90 temperature scale. Please note that the Wilson sound-speed equation below uses the IPTS-68 temperature scale.

The UNESCO equation for speed of sound in water

\(

\begin{equation} c(S,t,P)=C_W(t,P)+A(t,P)S+B(t,P)S^{3/2}+D(t,P)S^2

\end{equation}

\)

where

\(

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

C_W(t,P)= &(C_{00}+C_{01}t+C_{02}t^2+C_{03}t^3+C_{04}t^4+C_{05}t^5)\\ &+ (C_{10}+C_{11}t+C_{12}t^2+C_{13}t^3+C_{14}t^4)P\\ &+ (C_{20}+C_{21}t+C_{22}t^2+C_{23}t^3+C_{24}t^4)P^2\\ &+ (C_{30}+C_{31}t+C_{32}t^2)P^3\\ \end{split}

\end{equation}

\)

and

\(

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

A(t,P)= &(A_{00}+A_{01}t+A_{02}t^2+A_{03}t^3+A_{04}t^4)\\ &+ (A_{10}+A_{11}t+A_{12}t^2+A_{13}t^3+A_{14}t^4)P\\ &+ (A_{20}+A_{21}t+A_{22}t^2+A_{23}t^3)P^2\\ &+ (A_{30}+A_{31}t+A_{32}t^2)P^3,\\

\end{split}

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

B(t,P)=B_{00}+B_{01}t+(B_{10}+B_{11}t)P,

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

D(t,P)=D_{00}+D_{10}P.

\end{equation}

\)

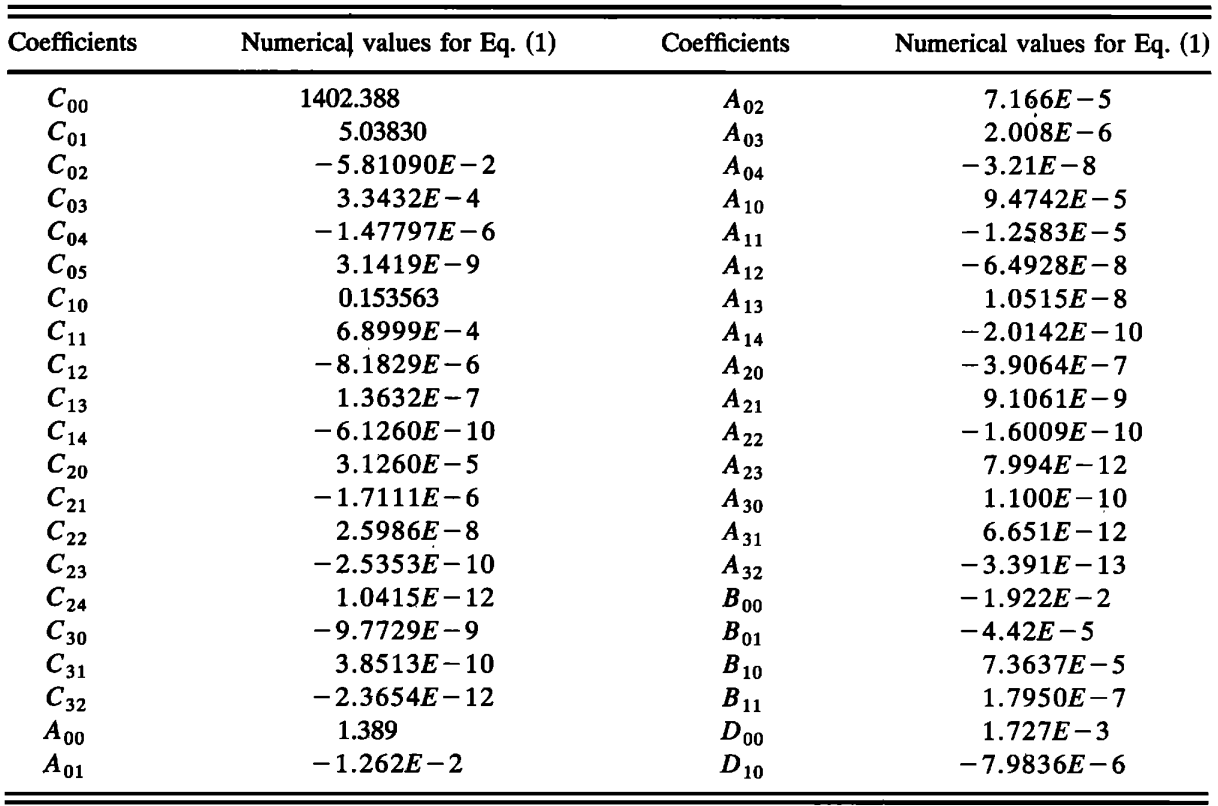

Please see below for the numerical values of the ITS-90 coefficients from Wong and Zhu (1995).

Numerical values of the coefficients for the UNESCO equation for speed of sound in water. Table from Wong, G.S.K and S. Zhu. (1995). Speed of sound in seawater as a function of salinity, temperature, and pressure. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(3), 1732–1736.

The Del Grosso equation for speed of sound in water

\(

\begin{equation} c(S,t,P)=C_{000}+\Delta C_T+\Delta C_S+\Delta C_P+\Delta C_{StP}

\end{equation}

\)

where

\(

\begin{equation}

\Delta C_T(t)=C_{t1}t+C_{t2}t^2+C_{t3}t^3,

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

\Delta C_S(S)=C_{S1}S+C_{S2}S^2,

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

\Delta C_P(P)=C_{P1}P+C_{P2}P^2+C_{P3}P^3,

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

\Delta C_{StP}(S,t,P)=& C_{tP}tP+C_{t3P}t^3P+C_{tP2}tP^2\\

&+C_{t2P2}t^2P^2+C_{tP3}tP^3+C_{St}St\\

&+C_{St2}St^2+C_{StP}StP+C_{S2tP}S^2tP\\

&+C_{S2P2}S^2P^2.

\end{split}

\end{equation}

\)

The Wilson equation for speed of sound in water

\(

\begin{equation}

V=1449.14+V_T+V_P+V_S+V_{STP}

\end{equation}

\)

where

\(

\begin{equation}

V_T=4.5721T-4.4532\times10^{-2}T^2-2.6045\times10^{-4}T^3+7.9851\times10^{-6}T^4

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

V_P=1.60272\times10^{-1}P+1.0268\times10^{-5}P^2+3.5216\times10^{-9}P^3-3.3603\times10^{-12}P^4

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

V_S=1.39799(S-35)+1.69202\times10^{-3}(S-35)^2

\end{equation}

\)

\(

\begin{equation}

\begin{split}

V_{STP}=&(S-35)(-1.1244\times10^{-2}T+7.7711\times10^{-7}T^2+7.7016\times10^{-5}P-1.2943\times10^{-7}P^2+3.1580\times10^{-8}PT+1.5790\times10^{-9}PT^2)\\

&+P(-1.8607\times10^{-4}T+7.4812\times10^{-6}T^2+4.5283\times10^{-8}T^3)\\

&+P^2(-2.5294\times10^{-7}T+1.8563\times10^{-9}T^2)\\

&+P^3(-1.9646\times10^{-10}T).

\end{split}

\end{equation}

\)

There are many studies looking at which equation is best to use, for example Dushaw et al. (1993) and Meinen and Watts (1997). In the upper water column (top 1000dbars), these equations tend to give similar results. Below this depth, however, experiments have found that they tend to diverge (e.g. Spiesberger and Metzger, 1991). Although the Chen and Millero/UNESCO equation is the internationally accepted standard (Fofonoff and Millard, 1983) for calculating sound-speed in seawater, scientists have questioned whether it is the best option for all applications (e.g. Meinen and Watts, 1997; Dushaw et al. 1993). In particular, Del Grosso’s algorithm is thought to be more accurate for calculating sound-speeds at deeper depths, where sound is moving slower (Spiesberger and Metzger, 1991; Spiesberger, 1993). Nevertheless, it is thought that Del Grosso’s algorithm, although accurate at calculating sound-speed for bottom depths, still produces sound-speeds that are slightly too fast for depths below 1000dbars (Meinen and Watts, 1997).

There are, of course, other equations available. Some of these equations take simpler forms, for example the Mackenzie (1981) and Coppens (1981) equations. Additionally, there have been updates and modifications on earlier equations. For example, Millero and Li (1994) published updated coefficients for the earlier Chen and Millero (1977) equation to take into account lower temperatures and higher pressures. Leroy et al. (2008) merged parts of the UNESCO and Del Grosso equations to address drawbacks of each.

Featured instrument

RBRconcerto³ C.T.D

Uniquely designed to determine salinity by measuring the conductivity and temperature of water. Conductivity measurements are performed using a rugged inductive cell that can be frozen into ice. Equipped with a pressure channel, the RBRconcerto³ C.T.D can also derive depth, density anomaly, and speed of sound. Learn more.

Explore popular CTD models

Related user stories

Monitoring sound in the Salish Sea: how scientists are trying to understand the decline of Southern Resident Killer Whales

Dr. Svein Vagle discusses his work using acoustics to better understand southern resident killer whale population decline in the Salish Sea.